Even without a manned mission to Mars, scientists have still been able to study the Red Planet’s surface thanks to the combined information from Martian meteorites. These meteorites were once a part of Mars’ surface which have made their way to Earth. Many of these meteorite samples are over a billion years old and can provide a lot of information about the Red Planet.

How Did These Rocks Get to Earth?

Considering no spacecraft has returned from Mars, no rocks have come to Earth from Mars via artificial extraction & collection. Rocks on Earth that have been authenticated as being of Martian origin have most likely come to Earth after asteroid impacts on Mars or volcanic activity on the Red Planet, both of which can cause rocks to eject from Mars’ surface. A number of these ejected rocks have found themselves caught in Earth’s gravitational pull and landed Earth’s surface.

How Do We Know These Rocks are From Mars?

Detecting that a rock is not from Earth is relatively easy, however knowing the point of origin can be far more difficult without having proper data on the body from which the meteorites came, with which to compare. As it stands, the meteorites we now identify as Martian were not always known to be so. Data from the Viking landers in 1976 provided enough of an information match to identify the properties of the rock samples to have a Martian origin.

Meteorite samples found before 1976 were determined to have been not from Earth due to their isotope ratios being inconsistent with our planet’s, but their point of origin was unknown before having the Viking data to for comparison. All of the Martian meteorite samples have had isotope ratios consistent with one another, further indicating their shared point of origin.

Are Martian Meteorites All Made Up of the Same Rock?

No, in fact there are 3 main groups of rock from Martian meteorites, which show the diversity of rock on the surface of Mars. These group names indicate where on Earth the first sample of each kind of meteoric rock was discovered. The three main groups of rocks are shergottites (first found in Sherghati, India in 1865), nakhlites (first found in El-Nakhla, Alexandria, Egypt in 1911) and chassignites (first found in Chassigny, Haute-Marne, France in 1815). The vast majority of the meteorite samples we have discovered from Mars have been shergottites. In addition to these three groups, there are other subgroups which provide an even broader look at the diversity in rock on Mars.

Do the Meteorites Get Contaminated Being on Earth?

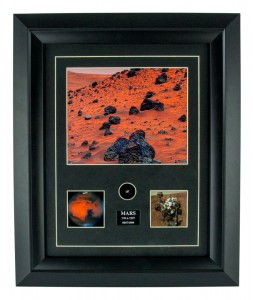

As Martian meteorite rock sits on Earth’s surface, it can become tainted. Even coming into basic human contact can negatively affect some findings about Martian meteorites. While many meteorites from Mars hit various portions of the African continent, many scientists prefer the samples that land on the surface of Antarctica, as they provide a lower risk of human contact. Pristine samples have only been discovered on Earth about once every 50 years, the most recent being NWA-7397 which landed in Morocco in 2011, and discovered in 2012.

What Do These Meteorites Tell Us About Mars?

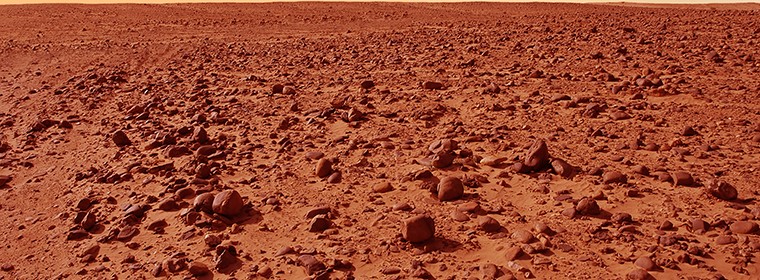

Meteorites can provide a lot of information about their places of origin, once we know what the place of origin is. In the case of Mars, meteorites can provide details of what Mars’ surface was like when the rock was initially dislodged, serving as a bit of a time capsule for Mars geography in years past.

Most Martian meteorites contain trace amounts of water vapor, which can be released from each sample by heating it up. This evidence helped indicate to scientists that there was once an abundance of water on Mars, even before NASA’s recent announcement. Given the age of most of the meteorite samples, the evidence of water vapor billions of years ago was not enough to prove by itself that water is still present on Mars.

Are There Other Ways to Get Samples from Mars to Earth?

With a manned mission to Mars still yet to be greenlit, NASA has been planning other methods of extracting Martian rock and bringing samples to Earth for further study.

In January 2015, NASA unveiled a proposal for a “tag team” of robotic vessels to visit Mars to collect Mars rock samples from both the surface and the orbit of Mars over the course of the next ten years. The next rover, expected to head to Mars in the year 2020, will include a feature to collect caches of samples of Martian rock and soil samples, leaving them behind for a future spacecraft to collect and a third craft to launch them from Mars and back to Earth. With even more pristine (and comparatively recent) samples, there is no telling what scientists may discover about Mars next.

-B. P. Stoyle

Scientifics Direct, Inc.